The place where I sit is peculiar, like the institution that shaped it (Creel, 1988), like the people who were brought here. It is a graveyard; it commands hushed tones. Its beauty is soothing to the heart, an opiate – an addictive, sensual beckoning. It is also a place of atrocity and pain. Killing fields. But I don’t forget. I remember. Their voices cry out to me. Listen! You can hear them too. Through the centuries, the stillness, the horrors…through the swamps, the mangroves, the sand dunes. Their spirits live in the rustling of the leaves, the waving of the palms – I can hear them. I close my eyes. I feel the breeze on my face. I imagine. I reflect. I listen. And I write. I sit in the Garden of the Muses at Brookgreen Gardens near Murrells Inlet, South Carolina, the former site of one of the largest plantations in history; now one of the largest outdoor sculpture gardens in the world.

The Gullah of South Carolina are among the most resilient people in the South. They came here as captives in chains, bound together in the belly of the whale, piloted by their European captors toward a world they had never seen, imagined, or knew existed. Knowing only their tribal African cultural traditions, they brought with them the customs of their rich heritage. One of those traditions was rice cultivation, which made them attractive and valuable to the slave traders. The voices that the kidnapped Africans heard from above – an amalgamation of multiple European languages – became their language, a patois called “Gullah,” which became their collective tribal name. Many descendants of the Gullah still live along the South Carolina coast. Driving down HWY 17 South toward Charleston, or south of Charleston toward Beaufort, you may notice their houses, distinctive because of their blue roofs. Blue, a royal, powerful, and treasured color, has a long tribal tradition of keeping evil spirits away.

Residents and visitors of South Carolina may not be aware of this history. South Carolina State Tourism departments have worked hard to soften and sanitize the horrors of slavery and its horrifying legacy of racism. For example, what used to be the Charleston Slave Market is now “Charleston Market,” with the telltale iron slave chains removed from both ends of both current markets. Many of our common colloquialisms reflect this racist history – the word “picnic” descends from the racist term for an enslaved child – “pick-a-ninny.” Donating scraps of food for the enslaved became “food for the fog.” Even historical documents reflect the racism and slave culture of the past, partially responsible for prevailing stereotypes of Georgians, the Spanish, and others. Women who owned enslaved people in the south were proud of the monicker “Revolutionary Womenhood,” which reflected not only the differences in the lives of colonial women from their British sisters but also reflected a new class of upward (and downward) mobility . It is in this land that we all now reside.

The dehumanization of the Africans kidnapped from their homes was integral to the success of the slave trade. One of the rhetorical tools that southern politicians, ministers, journalists, landowners and others used to succeed in this dehumanization was to convince the populace that the new arrivals were less than human, more like an animal than “like us.” Bogus science, “fake news,” fearmongering, and fabrications spun about Africans’ aggressiveness, sexual dominance, and tendencies toward violence were integral to the dehumanization of the Africans. Many of these propaganda techniques are like those used during segregation, an earlier topic in this three-part series honoring Black History Month.

Skilled engineers, craftsmen, midwives, doctors, cooks and farmers, Gullah’s influence throughout coastal South Carolina is evident. The giant locks that managed the tidal flow for rice production are still visible in the wetlands along the River Trail at Brookgreen Gardens. The descendants of the herbs and plants that they used for healing can be viewed at the Kitchen Garden. The seeds that they preserved and cultivated still grow and promulgate throughout the southern wetlands. The Oak trail, lined with huge oak trees, explains the use of these majestic trees for shipbuilding. Alligators still rest in the mud of the river, sinking down into the water – but still watching – as tourists hike nearby. This beautiful natural space is a testament to the people who cultivated it, built it, tended it, and honored it – the Gullah of South Carolina.

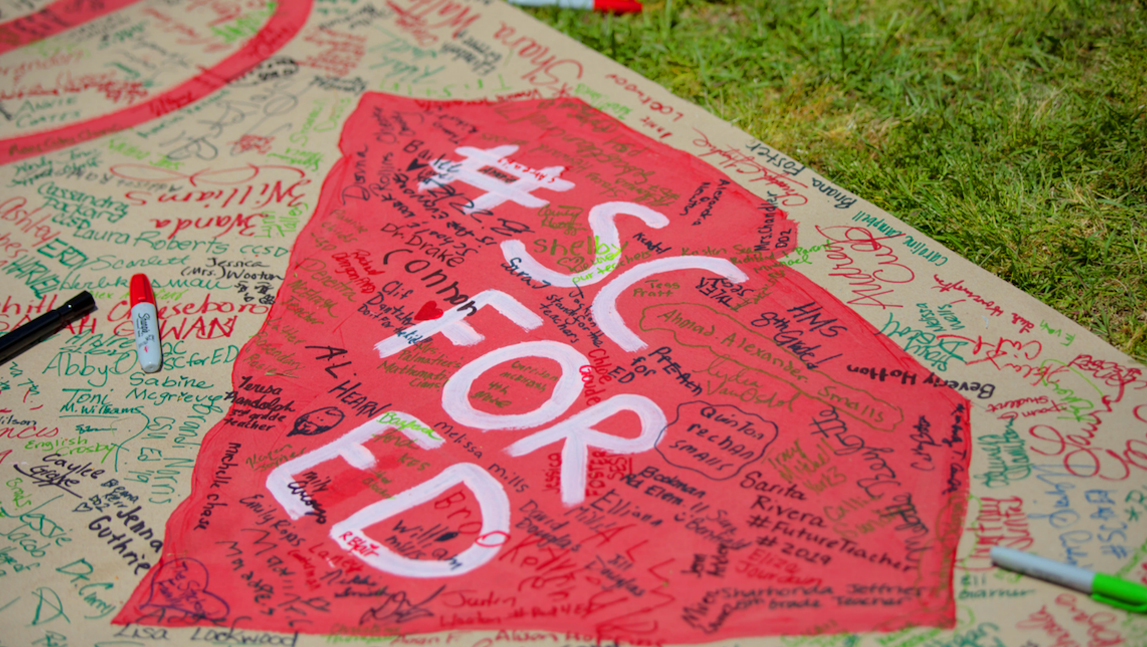

As we honor and celebrate the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s recognition in January, and celebrate Black History Month in February, it must become our honor to recognize and celebrate lives of all people, but especially some of the most resilient people in the south – the black and brown skinned residents of South Carolina.

Author’s Note: Portions of this article and a complete list of references can be found in the book, Talking through Death by Christine Davis and Deborah Breede, Published by Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group), New York and London, 2019.

References

“Colonial Life Said to Come Alive in Eliza Pinckney Letters” by Ellen Bryan. The News and Courier. 3/8/1972.

Creel, M. W. (1988). “A Peculiar People”: Slave religion and community culture among the Gullahs. New York: New University Press.

“Drayton Hall.” Middleton Place. pp. 217-226.

The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739-1762 by Elise Pinckney (Author/Editor) and Marvin R. Zahniser (Editor). University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC, May 1, 1997.

Our Story, Hosted by Bill Mozers. National Endowment for the Humanities. NY Pub TV WNET/13. SC air dates 10/9, 10/12, 12/25, 1975.

“Rivers and Regions of Early SC” – Articles from the SC historical and Genealogical magazine by Henry Am Smith Vol. 2. Published in Assn with the SC Historical Society by the Reprint Company Publishers, Spartanburg, SC, 1988.

Shutes Folly Island Early Quakers . Minutes of Quakers minutes meetings.

Talking through Death by Christine Davis and Deborah Breede, Published by Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group), New York and London, 2019.

Women in the New Eden by Anne Voth. University Press of America, Washington, D.C., 1983.