by Susan Hutchinson.

When I was growing up in Chicago in the 1960s, sporting goods stores sold handguns and rifles to sportsmen interested in hunting or just for target practice. There didn’t seem to be concerns about the weapon being used for criminal purposes and no extensive background checks were required. Firearms violence then was rare, even in my neighborhood which had numerous gangs.

Now, as we head into 2018, not a day goes by without the news media reporting some type of shooting — including all too frequent reports of mass shootings where the perpetrator used legally sold semiautomatic and fully automatic weapons.

Mass shootings, commonly defined as an event where four or more people are injured or killed by a single shooter within the same day, provoke public outrage. Every time such a tragic event takes place people shout that more gun control or background check laws are needed.

But are these actually an effective solution?

Background checks are limited to documentation found in various databases. Criminal records, mental health records and armed forces information are easily verified; however, the current background check requirement also covers the use of illegal drugs or confirmation that the buyer is not an addict, which is not always documented.

How do you add more criteria for things that should restrict sales, but can’t easily be verified?

If the buyer is not diagnosed for mental illness, not arrested or reported for domestic violence or not a publicly acknowledged racist promoting violence, there is no way to know whether the weapon will be put into the hands of a potential killer.

Many gun control laws have been enacted since 1934, with the most recent one being the Federal Assault Weapons Ban (AWB), signed into law in 1994 and then allowed to expire in 2004.

Like the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act of 1993 requiring background checks for purchase, it was a reaction to firearms violence that appeared to be out of control, especially incidents using assault weapons. The law restricted the manufacture, transfer or possession of firearms defined as semiautomatic assault weapons and magazines classified as large capacity ammunition feeding devices (>10 rounds of ammunition). The law did not withdraw weapons and magazines manufactured or possessed prior to the law going into effect.

Data on the effectiveness of the AWB shows that although mass shooting deaths appeared to remain steady for the first few years, the Columbine massacre in 1999 demonstrated that mass shootings with assault weapons were still a very real danger.

2017 data through November 14 also indicates that since the expiration of the AWB, mass shooting deaths were inconsistent year to year until 2014 when they began to show a significant upward trend.1

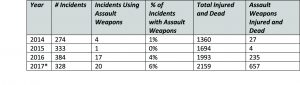

The table below breaks out the number of mass shooting incidents, with and without assault weapons, between 2014-2017.

*Data is through December 7.

The Las Vegas shooting on October 1, 2017 resulted in the highest number of fatalities and injuries from mass shootings in U.S. history. If this one incident had not occurred, the number of dead and injured would have decreased and the number of incidents using assault weapons still would have been higher compared to 2016.

The number of mass shooting incidents occurring in the U.S. in 2017 averaged 23 per month with 6 percent involving assault weapons.2

Although assault weapons may increase the number of victims per incident, should that be the sole focus for any new gun control legislation?

Mass shootings and the use of assault weapons is only a small part of gun violence in America. During 2017 there were 59,314 incidents of firearm violence, with 14,972 deaths and 30,253 injuries.3

The Brady and AWB laws show that reacting to specific mass shootings doesn’t address the big picture of firearms violence in America and a new approach to attacking the epidemic needs to be discussed and implemented.

1 www.motherjones.com

2,3 www.gunviolencearchive.org